The Name - Sold

In 1973, Halston sold his business for 12 million dollars to the conglomerate, Norton Simon. However, he remained as a managing director and chief designer at the company. Licenses were granted for the Halston portfolio which continued to diversify. After a few final successes such as Halston perfume, the decline began: Norton Simon was consumed by the conglomerate Esmark; Halston was forced to create a cheap fashion line for the retailer J.C. Penney. The "established" fashion world treated him with contempt.

The designer sank into depression which he tried to cure with sex, drugs, and parties at the legendary Studio 54. For the rest of his days, he was unable to rid himself of the deep regret that his own mistakes had led to the death of his brand. How could it have come to this?

Creativity Requires Attitude

Even the grandest visions require a consistent attitude. Without attitude, there can be no brand. In contrast, Halston firmly believed in being intuitively understood. He saw his individual creations as fragments of a greater oeuvre which could be explained through the genius of their creator. This should be sufficient, he thought, in creating brand identity. Especially in the fashion world with its changing trends and intense competition, only a few are able to successfully anchor themselves in the hearts of the public. This is because there is a fine line between the constant need for new creations and the common thread tying it all together which makes brand identity something tangible. Halston never managed to walk this fine line. What Hermès, Chanel, and even the popular Nike brand have in common is that they continually inspire their clientele, but at the same time - and this is the crucial point - they remain true to themselves. They leave it to others to ride the Zeitgeist wave. In the words of Ralph Lauren: "Fashion is over quickly. Style is forever."

Expanding the Brand: When and Where

While viewing the Halston Netflix series, you might notice a fictional commercial sequence in which Halston is multiplied against a white background and declares in many voices that he is now shaping everyday life with his products - "Halston for your every day! Halston for your world!". Luggage, home textiles, cosmetics - that is a far cry from the self-image with which Halston once took the fashion world by storm. Expanding the brand into new business areas while using a pre-established brand presence is one of the most demanding challenges of branding. Two questions must be kept in focus: the When and the Where.

First, the When: For a younger brand, exercising greater caution is advisable when expanding. Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren, the two American challengers to Halston, concentrated on the core business of the fashion collection in their early years. Expansion into new business areas came many years later. The recent announcement from Ferrari that they're getting into the restaurant business is only conceivable because the premium brand has built up a clear image over time. Second, the Where: It is imperative that the expansion of the brand support the market positioning. The goal must be that the expansion further enhances the brand. In other words, the question of the Where always pursues two equally important goals: entering a new business field and strengthening the brand with new capabilities. The extensive expansion of the Halston brand neglects the latter in a criminal way. The result is a too early decline in profile until the brand has completely lost its elasticity.

Branding Requires Performance

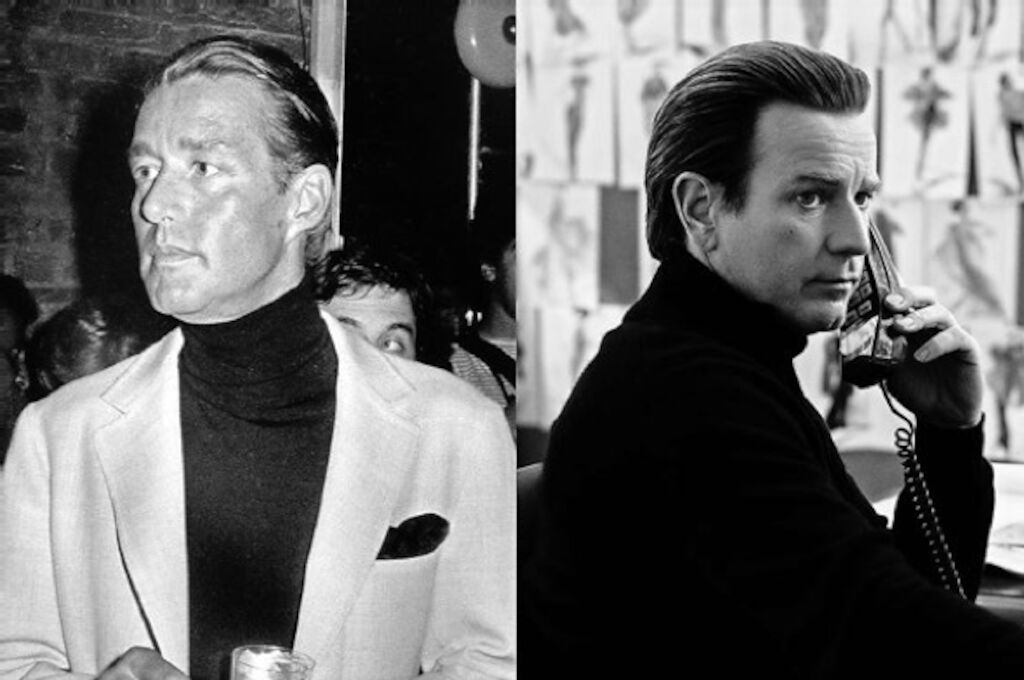

The debate on what makes brands successful is long and heated. At present, abstract concepts such as "purpose" and the often-cited "why" are dominating the discussion. But I am convinced that brands must most especially impress with the "what" and the "how" in addition to the important "inner purpose". Roy Halston Frowick, who elevated America to the fashion Olympus, thought he owed his initial success to his own unique and signature style. His bias cut, which did not cut the fabric along the course of the thread but rather at a 45-degree angle made for uniquely light and natural creations. They reflected the fun-loving, emancipated self-image which characterized urban America of the 70s. His "ultrasuede shirtdress" launched in 1972 built upon this and ensured its success its the masses. But what came next?

Innovation remained absent. It was not an abrupt fall, but the new creations lacked inspiration, the novelty value of the early years. Neither the grandiose shows nor the targeted self-marketing could fill this void. The principle is incontrovertible: Brands must impress through their core performance in order to be successful in the long term. Lacking this skill, brand erosion becomes imminent. How telling it is then - both in the Netflix series as well as in reality - that Halston was only once praised by the industry press when, free from commercial interests and restrictions, he designed ballet costumes for a girlfriend. In this act, he did what he was really capable of, what he really loved.